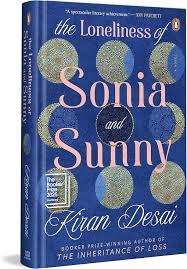

‘Must read’ book: The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny – Kiran Desai

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny is the kind of novel that doesn’t announce its emotional weight straight away. It unfolds slowly, almost casually, and then at some point the reader realises it has settled into them. Not because of a shocking plot twist or a dramatic climax, but because it captures something deeply familiar: the low-level, persistent unease of modern adulthood, especially when shaped by migration, expectation, and inherited ambition

Desai’s previous novel, The Inheritance of Loss, which won the Booker Prize in 2006, was an intergenerational story of postcolonialism, familial strife, and identity. With The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, Desai once again proves her superpower lies in her realistic depiction of familial relationships. She covers the pressures of Indian parenting on millennial kids, which somehow makes this novel feel contemporary and relatable to a modern Indian’s life

Set in the 1990s and early 2000s, at its centre are Sonia and Sunny, two Indian American young adults living in New York whose lives intersect through family and circumstance. They are not characters who barrel confidently toward self-discovery. Instead, they hesitate, drift, and second-guess themselves. Their loneliness is not loud or theatrical; it shows up in silences, in stalled conversations, in the feeling that life is happening slightly elsewhere. Desai treats this emotional state with patience rather than urgency, allowing it to accumulate rather than resolve

It’s a novel about families and cultures as much as it is about the relationship between Sunny and Sonia, whose families are neighbours and whose attempts to make a match set in motion their on-off liaison. Where Sunny dreams of journalistic success, albeit heavily inflected by the work of JD Salinger and Kurt Vonnegut, Sonia’s heart and mind lie in writing fiction. Alienated and alone at college in rural Vermont, she finds solace in Tolstoy, but is perplexed and provoked by the idea of magic realism and “the enticement of white people by route of peacocks, monsoons, exotic-spice bazaars”. The dilemma facing an Indian writer, she ponders, is one of obeisance to the West’s appetites and projections, and the lure of producing “stories cheapened by proliferation, decorative outside and hollow inside”

Desai’s solution to the problem in this immensely entertaining and generative novel is to dart continually between modes of representation and register. The gothic novel appears with the early introduction of the monstrous Ilan de Toorjen Foss, a narcissistic artist who seduces Sonia, suppresses her literary endeavours and then abandons her (“don’t write orientalist nonsense! Don’t cheapen your country or people will think that this is actually India … What Westerners did to you, you are doing to yourself”). The predicaments and predilections of Sunny and Sonia’s Allahabad relatives create a low-key bourgeois comedy: stranded single aunts, genteel impoverishment, the wrangle over a cook famed for his kebabs. These are reprised in higher style by Sunny’s widowed mother, the impossibly grand Babita, who is embroiled in a noir crime plot by the machinations of her late husband’s brothers and whose preoccupation with wealth and status cast light on the rapidly evolving strata of contemporary urban India

Around Sonia and Sunny is a carefully drawn cast of adults – parents, relatives, acquaintances – whose lives complicate any simple generational narrative. These characters often value stability, propriety, and achievement, but they are also marked by disappointment and emotional restraint. Desai portrays them with dry humour and empathy, showing how habits of silence and deflection get passed down as surely as cultural traditions

The novel moves between India and the United States, sometimes physically but more often psychologically. India is not idealised as a lost homeland, nor is America portrayed as a place of easy fulfilment. Instead, each location highlights different forms of dislocation. Characters carry imagined versions of both places with them, discovering that neither fully resolves their sense of unbelonging

The connection between Sonia and Sunny develops slowly and awkwardly, shaped by hesitation and emotional caution. Their interactions are tentative, charged with possibility that never quite settles into certainty. Desai excels at writing these moments — conversations that almost open into intimacy before closing again. These scenes capture how loneliness can persist even in proximity, and how connection often feels more fragile than expected

The connection between Sonia and Sunny develops slowly and awkwardly, shaped by hesitation and emotional caution. Their interactions are tentative, charged with possibility that never quite settles into certainty. Desai excels at writing these moments — conversations that almost open into intimacy before closing again. These scenes capture how loneliness can persist even in proximity, and how connection often feels more fragile than expected

Plot, here, advances through everyday situations rather than dramatic turning points: family gatherings, academic spaces, conversations that misfire. Meaning accumulates gradually. A small remark later reveals emotional weight. A seemingly stable relationship shows its cracks. The novel trusts the reader to notice patterns rather than wait for revelation

There is also a steady undercurrent of humour, particularly aimed at intellectual and cosmopolitan spaces. Desai gently skewers pretension and self-awareness without cruelty, grounding the novel in a recognisable social world and preventing its melancholy from becoming overwhelming

Desai doesn’t aim for neat resolution. The book ends without decisive breakthroughs, leaving its characters still uncertain, still unfinished. This may frustrate some readers, but it feels true to the book’s understanding of adulthood as something ongoing and unresolved. What ultimately makes the novel work is how closely its form mirrors its emotional concerns. The drifting plot reflects the characters’ inner lives. Absence shapes the story as much as presence. Rather than offering answers, Desai offers recognition – and for readers attuned to its quiet, thoughtful rhythms, that recognition is powerful

What a shame it didn’t win the Booker!

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.